Alternate title:

“Why Seaboard Peru and USCGC Resolute will be getting holiday cookies while the Errol Flynn Marina will be getting a lump of coal for.the.rest.of.my.life”

Wednesday May 9, 2012, Port Antonio, Jamaica

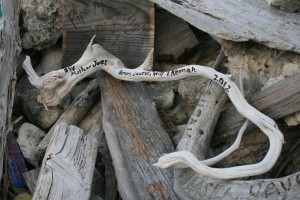

For the last several weeks, we’ve been in touch with the veritable weather guru, Chris Parker, to determine the best weather window for our biggest passage to date: a four day and three night (80-odd-hour) run from Jamaica to Providencia, Colombia – which is is actually about 120 miles off the coast of Nicaragua. This was the first big passage for Mother Jones (The Bahamas to Jamaica was 48 hours) and also the biggest passage on the way to Panama. Because we’d be in open water with no place to stop, it was important we picked a good weather window for the safest and most comfortable passage.

Chris had been predicting a Friday departure for over a week. So, we provisioned, mapped out our easy 3-hour shifts: Will is 9pm-12am, I’m 12am-3am and D is 3-6am and we all take the days as needed.

We planned, looked forward to and had a nice bon voyage dinner with our friends Hans and Linda on Wednesday, knowing we could always finalize any last minute prep on Thursday.

As an aside, we first met Hans and Linda in Portobelo, Panama one year ago and now meeting one year and many, many miles later in Port Antonio, Jamaica was a thrill for all of us.

They were happy to show us around and give us the skinny on the area as they had actually been hanging out in Port Antonio for weeks before Mother Jones arrived. While they were certainly making the best of it, their time in Port Antonio was likely to drag on beyond their choice: they were sorting out replacements due to losing their mast and all of their rigging on the passage from Cuba to Jamaica. Theirs was a story of a simple, yet critical, part giving way along the passage. In turn, their mast lost stability, lurched aft and threatened to fall on top of the cockpit (where they were both standing). Narrowly missing the cockpit, the rigging and full sails landed in the water, but still attached to the boat. With their sail creating a virtual drogue (an underwater kite of sorts used to slow a boat down in high wind and seas) and now turned abeam to the seas, a quick use of cable cutters freed them from the certain fate of rolling over (but perhaps not rolling back up) and they watched it all sink away and then rode, now mastless, with engines on the 100 or so miles remaining to Port Antonio. It’s a harrowing tale in which no sailor likes to be cast. But they survived fortunate enough to have as their only injuries the myriad papercuts from dealing with all of their insurance companies’ paperwork.

After a wonderful dinner, we headed back to Mother Jones and checked in with Chris. And, as it’s wont to do, the weather changed: we needed to leave Thursday – aak!

May 10, 2012 – Day 1, Port Antonio, Jamaica

Thursday morning we confirmed the weather window and given the storms predicted for Sunday night, Chris says if we are going to go, we need to go now or wait at least another week for another window. At $15 a day to anchor, the guys already having spent three weeks longer in Jamaica than anticipated and with some friends arriving in Bocas del Toro, Panama next week, we were eager to get out of dodge*.

*Seasoned sailors will say the #1 way to get in trouble on the ocean is to keep a schedule (such as meeting guests at a certain port). The reason this invites trouble is that one’s emotions, especially impatience and feeling of excited obligation tend to override the normal common sense you’d use to stay put when the conditions aren’t ideal – you go anyway because you “have to” be there by X day.

Day 1, 10:30am – It’s been was decided. We were going, like now.

We battened the hatches (yes, that’s a real thing), stowed everything that would could come loose underway, and otherwise finalized preparations on the boat for the long passage. One thing we noticed while pulling up anchor was that the engine sputtered just a bit – no worries, probably just some air in the line from sitting for 3 weeks. We’ll just clear the line before leaving, right? (Well, as it turns out, wrong.)

With the fuel line cleared, off we went, making one last stop at the dock to tap off our water tanks and clear out of customs and immigration. As we sat at the dock, we noted a large crowd gathered on the shore by the police dock. “What’s up?” we wondered.

As it turns out, the crowd had gathered around the police dock because earlier in the morning the small force had retrieved the body a young fisherman from the harbor. As word spread, so the crowd increased. Given that Port Antonio is relatively small town, I’m sure many in the crowd knew this young man whose boat had capsized the previous night in the East Harbor and unfortunately, without a life jacket or knowing how to swim, he drowned. Apparently it’s not unusual for many who live in this area (on an island, on a port, and who make their living on the water) to never learn to swim. It’s unimaginable to me but tragic nonetheless.

It was also yet another reminder to us of the perils of the sea. And, we couldn’t help but ask ourselves “was it more: perhaps a bad omen for our long passage?”

Now, I’m generally not a superstitious person, but becoming a sailor has definitely brought out this side of me, as it’s known to do for so many who test their skills and preparations on the merciless seas. I suppose we’re all looking into things for some sense of control of what may be to come and one can get lost in the wondering:

So, a body found in the harbor doesn’t seem like a good sign, but what shall we make of this butterfly we’ve never seen over the past few weeks in Jamaica that has come to playfully flutter about the cabin while we await departure – that’s got to be good, right? And, finally, with the harbor of Port Antonio behind us, just after 3pm, we get one final omen, traditionally one of good luck, as a dozen or so small dolphins play in our bow – nothing to worry about!

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1LdTHVNMNB4&feature=youtu.be]

As we motor along Jamaica’s northeast coast, several quaint little coves we didn’t have time to explore offer small pangs of “wish we could’ve stayed longer,” “what’s around that bend” travelers-remorse. But, it’s all good, we figure, we’re on our way!

Day 1, 6:30pm – As, the sun sets, beautiful rays of sunlight filter through the clouds over Jamaica’s blue mountains, and we turn our sights south. Spirits are high and all is well on Mother Jones.

Our route takes us first east across the north coast of Jamaica and then southeast to Providencia. Although you can take the rhumb line (the straightest course between two points), given Chris Parker’s advice, we set our course for a more generous angle for the first 24 hours or so to avoid some “whirlpool-like” currents along the way.

So, instead of using the full force of the trade winds and following seas, we expect a little more bumpy ride for the first day or so as the waves and wind come at a broad reach for us (diagonally across the boat’s rear).

This bumpy ride has rendered Will and I a little seasick – after all, I’ve yet to get my sealegs back after a couple weeks away and the super-calm anchorage in Port Antonio offered no gentle easing in (for me) or practice for those prone to a little malaise (Will).

Aww, well, we soldier on. I even feel up to making a nice pot of gumbo from the fresh okra I got here in Jamaica – yum! Shortly after dinner, I retired to get some rest before my midnight-3am shift at the helm.

Friday, May 11, Day 2

12am

Awakened by Damon, I ready myself for my shift. It’s been a bit bumpy but nothing really to report. I settle in to our course: sails up with the motor on for an extra push and the auto-pilot is making our trip easy. I’ve a few granola bars, apple sauce and a Nalgene full of fresh water to keep me fueled up, and keeping me company on this calm, clear night, I’ve plenty of Ani Difranco, Dixie Chicks , and The Judds (ok, there were a few guilty pleasures ala Nicki Minaj and Katy Perry, thrown in there, too [thanks, sister J]). Given the events of the last couple of weeks, I decide to have a cosmic road-trip date with my best girlfriend and her sweet new baby and that’s about how it went: lovely and expansive. Until . . .

Day 2, 2:30am

Nearing the end of my shift, the engine started to sputter and Damon jumped into the cockpit from his resting spot in the salon. A “Hmmm” entered both our heads, but we weren’t really alarmed. After all, it had happened before: once when we were en route from Long Key to Angelfish Creek in Florida and just needed to change the fuel filter, and, of course, it had also happened another time “before” as in 12 hours before now when we were in the harbor. Both times we were able to troubleshoot and replace the filter or bleed air from the lines to get back to operational in short order. So, we figured a simple solution may be at hand. In the mean time, we could just keep sailing until first light when we could diagnose and make repairs without the added drama of darkness.

Day 2, 9am

A few hours after dawn, we change the filter and so far so good. No sputtering, but you know how mechanical problems go on a long voyage: sure, everything is fine but where everything was actually “fine” before, now it’s a wondering-fine as in “did that really do the trick?.”

Day 2, 10:30am

Everyone is up. The sails are up, we’re charging our batteries on solar and continue to run the motor (testing it). Everyone’s in good spirits. A little tired from our three-hour shifts, but with a three-person rotation (and the auto-pilot keeping us from having to actually steer the whole time) we’re feeling relatively comfortable.

I’m at the helm and D and Will seem to be working on something inside. Brother stuff, I’m sure.

I’m doing my every-few-minutes-360-scan for boats, flotsam, jetsam, “weather” (which we’ve come to know as “not good weather”) and in a flash I think I see, do I see?, a fin, then two, penetrating the surface of the waves not 10 yards from the boat. Sure, we’ve seen dolphins plenty of times from the boat (and it’s always a fun surprise for the crew (except for Kemah, who completely loses it), but these fins are different. I’m not scared – they’re not sharks – but what are these thick, dark dolphin-esque creatures with small fins – are they tiny whales???

As I scan the waves for more evidence that yes, I am actually seeing whales in the wild for the first time, and as I open my mouth to holler for the guys to come look, I shortly realize they are not talking about “brother stuff.” They are, in fact, quickly diagnosing a new problem: the bilges in our starboard aft (right rear) hull have collected enough sea water to soak the carpets, threaten the bottom of Will’s mattress, and certainly spring us all into action.

The whale-watching will clearly have to wait. (Except for Kemah, who for some reason was not harnessed in at that moment, decides to take advantage of his freedom and almost gives up his ghost before we catch him bobbing on the swimsteps trying to get a closer look at the whales – gawww!)

Whenever we’ve had water in the boat, there are several stages of diagnostics which occur: what type (fresh or salt)?, how much (are we sinking or can we “manage” this)?, and from where?

The water was salt, the amount was manageable and likely coming through the open design of our stern as a result of the following seas. Okay. We can deal with this.

And, within 5 minutes, all of Will’s stuff is carted into the salon, wet carpets come up and into the cockpit, the mattress comes out (not too wet) and finds a resting place in the companion way leading to the head. Just like *that* my tidy little boat is littered with all sorts of “stuff.”

Sure, you might be thinking, “jeezy, chreezy, Laurie, don’t you have better stuff to worry about at this point than a tidy salon?”. In some ways, “yeah, totally, water into the boat breaks Cardinal Rule #1 for boating (#1 water out, #2 you in) and that is definitely my top concern.” But, I find it of the utmost importance to keep things tidy and accessible on the boat so if, and in our case, when things go awry, you can easily get to what you need to fix the problem. Plus, it’s just my personality that when I start to feel out of control the easiest way to begin sedating myself is to clean: it gives me the sense of orderliness I desperately crave (“water in the boat? Time to clean the stove!). Or, in this case, “Let’s arrange the wet-cushions in the best quick-drying fashion (read: logical as well as eye-pleasing)”. Seriously.

Once the cabin was clear, D and Will got to work bailing the bilges. On the few times this has happened before, we’ve found the best plan of action is for me to keep busy (this time at helm) while I ignore the buckets and buckets and buckets of seawater being carted past me and dumped overside back to where they belong.

Once bailed, we run the fans in the cabin and the bilge pumps on the regular and generally keep an eye on the situation (a very slow leak).

Day 2, 4pm

By late afternoon, with the following seas continuing to (slowly) fill our bilges, but further down our dogleg course, we change course and into the evening, we notice the starboard bilges slowly run dry. Pfew.

It’s smooth sailing from here, right? All we have to do is maintain course and remember to keep enough charge on the batteries to run the instruments overnight.

Day 2, 10:30pm

Our change in course has been treating us pretty well. We’re now going directly with the wind and waves, our sail is trimmed perfectly, our ride is comfortable and we’re relaxed.

Clearly we’re a little too relaxed as I wake up 30 minutes into Will’s shift by our battery alarm letting us know we’re out of power (we’ve been sailing all day -no motor- and night but run down our solar supply). Fine.

Aside from being irritated from the rude awakening (I’ve always been a bear to wake when not ready, right, family?), Will and I are not feeling stressed (and we hesitate to wake D, who is conked out, clearly needing rest). We definitely need power to run the navigation equipment, lights and for the most comfortable passage, the auto-pilot. But, we do have a backup generator which we generally reserve for super-important tasks like microwaving leftovers, and the very rare occasions like this where, like we’ve run the batteries down so much that we need the generator to kick-start the motor. No worries, right? Wrong.

I take the helm, while Will yanks on the generator’s pull-cord to no avail. Great. The generator lives in the starboard swimstep compartment – the same one that is the gateway to the starboard cabin leak. It’s likely soaked. Fun times.

At this point, D pokes his sleepy head out and starts going to town on the generator. Completely frustrated, knowing that my shift will come soon, I resign myself back to bed – as if I could get some sleep. From bed, I can hear the impotent pulls on the generator which culminated in an award-winning R-rated exclamation when the pull-cord was actually pulled free and clear from the generator. Awesome.

In situations like these (like I’ve been through this before), I’ve found it’s not helpful to freak out and completely lose it. Instead, I run through the best-worst case scenarios:

- Best: we have enough charge to run our nav and lights eight hours until sunrise when our solar panels can recharge our batteries (definitely not enough to run the auto-pilot so we’ve got eight hours of manual steering ahead of us, okay)

- 2nd best (aka not best at all): all our power goes out, we use our handheld GPS devices and Open CPN charts on our fully-charged laptops to navigate and if we encounter another vessel we can use our spot light (also fully-charged) or worst-case flares to signal our position

- Worst-lite: we have no lights and no nav causing us to get run over by a container ship in the middle of the night, or we run aground on one of the cays we were supposed to pass by tonight

- Worst: Before scenario 3, Worst-Lite, I kill Damon and Will for not charging the batteries with the engine or the generator before we lost light (and before my shift), and toss them overboard, therefore I have no one to throw first in front of the container ship or onto the reefs (I’d never do that to Kemah)

Not being one to dwell on the worst (just one to smartly consider the worst), I wake at 12am still highly irritated but willing to have faith. Turns out, we’re fine as we all steer, sail and wait until morning’s light allows us to charge up again.

Day 3, Saturday

9am

A few hours after dawn, the batteries are charged up again, we kick on the engine with no trouble and fire up the auto-pilot again. Awww, we’re all ready for a little respite. While it’s certainly exhausting to steer 100% of the time (24 hours a day), there is a certain rhythm I get into dancing with the seas, charging up her crests and then surfing down her wakes that I rather like. It definitely feels more natural (all the way down to my four-hours-on-my-feet-numbing-toes) than the back and forth of the auto-pilot’s clack-clack-clack course corrections with.every.wave.

Day 3, 12pm

At noon, we head up to the bow to take K “out”. He does a great job shimmying up the length of the boat allthewhile harnessed into one of us, while we’re harnessed into the boat. But, drat. We get up to the bow so he can TCB, and dangit dolphins have come to visit again – and, Mr. K does not care for their visits. Actually, to say he “does not care for their visits” is an understatement. He completely loses his S – “barking” doesn’t describe the warbling noises he belches out as he whips his head back and forth between the dolphins to us (“What the what!?! Are y’all seeing this?!?).

Needless to say, no “business” was done. Aww, well.

Once we got K safely back in the cockpit, we ventured out again on the bow to take in the show. It was nice. Nice to be on the bow, blue water below, silver streaks of muscle darting beneath us, narrowly yet purposefully missing the boat. It was also so nice to just stop, look and see the space we – D and I – were occupying. Up on the bow, the space we dreamed of was there for the taking in: blue, expansive, crests of white foam off gentle, rolling waves and the wind – just the sounds of the wind filling our sails and all of our senses (thanks, JD, for the inspiration). Although I’d definitely had many moments of apprehension about sailing in general and this long blue-water passage in particular, this wasn’t one of those moments. And it was nice, so nice.

Day 3, 12:30pm

Back in the cockpit, high off our moment, I’m looking forward and what do I see, but, yes (ugg) a little tear in the leech line on the jib. Fortunately, it’s only about 4 inches off the bottom edge of the sail and only about 4 inches long. D shimmies back up to the bow with every sailor’s best friend (duct tape) and we make a make-shift repair that will hopefully keep it from running up in the 36 hours we have to go.

Day 3, 3pm

This afternoon, on our every-few-hours-bilge-check routine, we get a *fun* new surprise: the aft port bilge is full – fan-f’ing-tastic.

Because we’re definitely keeping a running tally of what’s up, here’s the damage so far:

- An engine with suspicious sputtering tendencies

- A broken generator (our emergency back-up power supply)

- Wet bilges in both aft cabins (aka sea water getting into the boat at a rate of a about a quart an hour)

- A small tear in the jib

Okay, we’ve got our sails, we’ve got power (solar and the engine is on), we’ve got navigation, we’ve got steering, we’re floating, and we’ve even got auto-pilot!

We can get through this. We will get through this.

Every hour we check the bilges and pump or bail to keep everything under control. We keep an eye on our battery supply and soldier on. After all, we only have 180 nautical miles (30ish hours) to go, right?

Day 3, 4:25pm

This afternoon, as we motor-sail along, the engine decides to prove our mistrust right: sputter, sputter, sputter. It’s clear that the engine is not getting enough fuel, like it’s starved. So, D bleeds the fuel lines and we start to hand-pump the ball to force the fuel into the engine. While we still have the sails, if we have to keep pumping like this (one person on the helm and one person on the pump), it’s sure to be a long night.

Day 4, Sunday

12:30am

Eight long hours later, we’re sailing on through the night. I came to my watch early, around 11:45 and have now been wrestling the high seas (10-12 feet) and healthy wind (12-20 with gusts to 25) for what feels like much longer than 45 minutes. Keeping Mother Jones on course while we sail wing-on-wing is proving challenging for me in these conditions*.

*Sailing “wing on wing” is normally done when the winds are coming from behind (as they were for us). Both sails are positioned in opposite fashion across the boat (our main was full to starboard and our jib full to port). It’s called “wing on wing” because the sail position, when viewed from the front, causes the body of the boat to look like a bird with two “wings” (the sails full of wind) coming out from the sides. In order to position our jib out to the side, we use a whisker pole which is basically a metal pole that sticks one end of the sail out 90 degrees from the mast to make the “wing”. Futhermore, we now know that we shouldn’t have been sailing wing on wing in these conditions. And, even furthermore, the moment I felt out of control, I should’ve stopped and changed strategies. Now, I know.

While one might think that keeping on course is just about making sure we don’t go too far from the little line on the GPS, in these conditions keeping on course also has everything to do with being in a good position relative to the waves (so they’re not crashing on you in a way you don’t intend) AND it’s important to maintain your course relative to the wind (winds and waves aren’t always on the same page).

In my case, we’d climb a wave which would want to pull us down the face to the starboard but I needed to stay port to keep the main from jibing unintentionally.

FYI – jibing is when the boom swings across the boat because the position of the boat:wind changes and the sail is now full on the opposite side. Jibing in and of itself doesn’t have to be alarming or dangerous if it’s done in an intentional manner in which the crew is all aware of the change. An uncontrolled or accidental jibe is one of the most dangerous things to happen on a boat as the force of the full sail swings the boom suddenly across the boat. If you’re in the way, and your head isn’t taken square off your shoulders, you’ll surely be knocked overboard, unconscious, or some other version of “seriously injured.” Luckily, the way our boat is designed we are at little risk for serious bodily injury (the boom is above the cockpit by several feet) but accidental jibing will definitely, violently stress our traveler (the tracks the boom runs on) which eventually would create a break resulting in a inoperable boom (no use of the main sail = bad). Also, literally while I write that “we’re at little risk for seriously bodily injury” from an accidental jibe, I’m looking at D, whose nose was simultaneously slammed and rope-burned from the lines running to the boom during one such accidental jibe. Ironically, just before it happened he said “you know this is bad, like really bad, right?”. To which I replied, “yep, yep I do” and then WHACK.

As I struggled to keep us on course, we zigzagged to port, then to starboard, I’ve got my eye on the main sail (which is ever-threatening and then does jibe back and forth), my hand on the lines to the boom, (which I pull tight when it jibes to port and then loosen when I’ve gotten back on track to starboard), AND I’ve got another on the jib which is also ever-threatening to change positions on me slamming the whisker pole into the stays (heavy duty cables which hold the mast up).

For land-lubbers, the best driving analogy I can give is like this:

Ever driven on a stretch of highway during high winds and feel the push of Mother Nature cause you to compensate your steering? OK, so take that, pretend the road isn’t flat but a short series 10 foot hills, the roads are that kind of wet when the rain first starts to fall when the water mixes with the oil and you start to slide and fishtail. Ok, got that? Now, a couple more things: pretend that if you don’t stay as true to course as possible, you risk your axles breaking as they slam side to side when the wind pushes you one way, you correct and it slams back the other into the original position. Oh, and one more thing, it’s dark and you have no headlights. Now, you got a pretty good idea of what the conditions were like, right? Are you having fun yet?

So far, for at least a half-hour, I’ve kept it just under control when a 25-knot gust hits us from the beam whacking out any semblance of control, and just like that, before I can exclaim “All hands on deck,” the whisker pole slams into the forestay, bends in half and then promptly slices directly through the jib. Shit.

All I can do at this point is keep steering while D clips in, tightens the whisker pole so it won’t slice through him, shimmies up on deck and begins the process of untangling the mess – in the same conditions that got us into this pickle.

He gets the whisker pole free and sinks it. He cuts the jib lose and climbs back in the cockpit to roll it in to no avail.

12 inches from me, D is insistent I try to bring the boat about (you turn into the wind to make the sail slack to roll it in). “I’m trying! I can’t!” I anxiously reply as I struggle with the steering – and not in a wind+waves=hard kind of way, but more of a steering is out, as in NOT WORKING kind of way. For real!?!

But, there’s no time to lament, poo-poo and “why me?” so we focus on getting the main in. I’m able to slide to port allowing him to furl it, quickly.

And, then finally we have a second to think.

Now, in the darkness, with the drama of the last five minutes nipping at our heels and the beating jib leading our way, we somehow find a moment to focus on “what’s next.”

“What’s next?” I ask D. Like “pull over” is an option. Wouldn’t that be nice?

We each quickly and silently run through all the distinct flavors of the jams we are in:

- We just ripped a huge hole in the jib = not good

- Our main is intact but furled because of the high winds = good, but not useable = so, not ideal

- We haven’t used the engine for hours because it’s been reliably unreliable = not good

- The starboard cabin leaks seem to have stopped = great

- The port cabin leaks are still with us = not good but manageable

- Navigation, communication equipment and power levels are all on the level = awesome

- And, last but definitely not the least of our problems, we have no steering = not good at all

Having no steering and no propulsion 150 miles from the nearest port (which is in turn 150 miles from the mainland) is not good at all. But, hey, at least we’re afloat, right? Ugg, sometimes being an optimist is exhausting.

Breaking the silent stares of concern and shell-shockery, D looks at me and says “I think we should call it off.”

“What do you mean?” I say.

“I think we should call it off,” he repeats.

“More words,” I encourage.

“I think it’s time to call the Coast Guard.”

“Okay.”

Day 4, 12:45 am

Yep, this is really, actually, in fact happening. We are a disabled vessel. We are 150 miles from the nearest port. We are in open water.

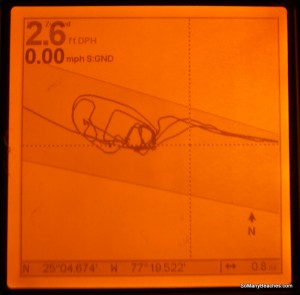

We seem to have 15 degrees of steering capability, which amazingly is stuck on our course. So, we figure the best case scenario is that we drift, on course, as far as we can get allthewhile using our comm equipment to reach out for help.

As far as comm equipment goes we have a SPOT tracker and a VHF. Sure, we’d absolutely love an SSB, but in terms of what we “want” or “would love” right about now, suffice it to say we’re focusing on different stuff.

Anywho, the SPOT tracker is a basic satellite-based GPS which tracks our position and has the capability to send basic messages (a “we’re okay” or an “SOS” message) to designated contacts (my mother is one). Given all of our previous messages were “it’s all good” messages delivered via email and Facebook, we expected my mother *might* check her email in about SEVEN hours, get the distress call and then begin emergency procedures.

We didn’t know if the SPOT might send a distress message on Facebook or on our blog’s map but we thought maybe, just maybe, one of our friends up at 1am on a Saturday night/Sunday morning might also be of some assistance (note to selves: make someone who is up at 1am most nights an emergency contact – I’m looking at you, Ash D).

But not to worry too much, we’re not just relying on our SPOT, we do have the VHF. Our VHF has the capacity to transmit line-of-sight, which in practical terms means we can transmit and receive radio contact within about 30 miles. Given we’re out in the middle of nowhere, we didn’t count on help coming right away, but there was nothing to lose by trying. It was decided, every 15 minutes we’d PAN PAN and that we did.

So, at 12:45am, we started transmitting our PAN PAN, which is just below a “Mayday” in terms of an emergency (“Mayday” is imminent danger: sinking, fire, pirates, heart attack, etc).

“PAN PAN, PAN PAN, this is Sailing Vessel Mother Jones, 150 miles northeast of Isla Providencia, we are a disabled vessel requesting assistance from any vessel in the area. If you read me, please come now. I repeat, PAN PAN, PAN PAN, this is Sailing Vessel Mother Jones, 150 miles northeast of Isla Providencia, we are a disabled vessel requesting assistance from any vessel in the area. If you read me, please come now.”

Nothing. Radio silence. Waiting. And then more waiting.

About 5 minutes after our initial distress calls were sent out, D looks at me and says “I have an idea.” OKAY!

While we had changed the filters, bled the lines, pumped the engine by hand from the fuel tanks through the lines to the engine, he thought “let’s eliminate the middle man and just run the line from the tanks straight into the engine.”

“Let’s do it.”

D and Will try this plan while I continue to “steer.” Luckily, careful planning had given us enough power reserves to try to turn the engine over and “Eureka!” it worked.

Now, we had propulsion with limited steering. Alright, we’ll take it.

We still had to pump the engine by hand several times a minute but doggone it, *something* was working and we were moving forward.

At this point, at a little more than 5 knots, we thought maybe, just maybe we could limp into port before dark (you never want to arrive in an unfamiliar port after dark, but you never want our problems either). Maybe we could get close enough and another boat could tow us in or maybe even in the worst case scenario, if we ran out of gas for Mother Jones but were close enough, we could unload the dinghy and tow ourselves in if no other boats answered our call.

Sure, it wasn’t an ideal plan, but having any options at this point was a luxury we weren’t taking lightly.

And so it went. For the next two hours, we pumped the engine, we PAN PAN’d, we waited, we motored (mostly on course), we pumped some more, we PAN PAN’d, we waited, we pumped, we PAN PAN’d and we waited.

At one point, with all three of us up and at least 16 hard hours to go, I hit a wall and decided to lay my bones down for a bit. Of course, there’s no real sleep available in situations like these, but there is rest. Sweet, sweet rest punctuated by the reality of Damon’s PAN PAN’s every 15 minutes.

Day 4, 3:46am

Three hours after our initial PAN PAN, a voice on the other end of the radio answers Damon’s call : “Mother Jones, this is Seaboard Peru, what is the nature of your distress?.” From my resting place on the salon cushions, I almost hit the roof.

Amazing, relieving, eye-watering, alleviating, soul-lifting, buoying – pick an adjective ‘cause I cannot begin to describe how wonderful it felt to have someone on the other end of the line. We were not alone.

For the next twenty minutes of so we and the Captain of Seaboard Peru, a cargo vessel, work through the typical Q&A associated with these types of situations: “what is the nature of your distress, what is your position, how many on board, are there medical emergencies”, etc.

We ask about a tow to the nearest port. He isn’t sure. He is awaiting word on what to do from his superiors in Miami. We are on course to Providencia, Colombia. They are headed to Panama City . . . Florida.

He asks us to slow our course, is two hours from us but will come to meet us, is still unsure about a tow.

Damon and I discuss: if he is unable to offer us a tow, what is the benefit of slowing our course? Remember, Chris Parker, the weather guru, predicted storms for tonight and we are definitely not up for that.

Sure, we have limited steering, limited propulsion, but we are on our way. It’s slow-going, definitely not ideal, but should we give up this course for another unknown? Do we risk the possibility of slowing down (and not arriving by nightfall, when the storms are predicted, if we even can) for this unknown possibility?

With a healthy fear of the predicted weather weighed against the promise of rescue, we decide to reduce speed but keep course. We have some wiggle room to make landfall by dark (we’re clearly feeling emboldened by our radio contact and limited systems.

We’re feeling good.

And then Seaboard Peru drops a bomb on us: “are you prepared to abandon ship?”

Damon and I shoot each other a “what????” look. I mean, we’re not sinking, so why would we abandon ship? Surely, no life is worth a piece of property but “really? abandon ship? are we at that point, really???”. Fuuuuuuuck.

And, it hits me. A single, hot, fat tear runs down my face carrying my fortitude along for the ride.

As it always goes, we have just run south of our insurance zone. Our (meager) life-savings rests in between these hulls. We had always figured that if and when we decided to leave the boat, we could take whatever we got from the boat sale and start out again with that.

With the possibility of “abandoning ship” on our minds, we both silently recount how months earlier in another moment which was not-at-all-life-threatening but containing a similar lack of faith, I blubbered to D “we were so secure, if we go back again, we’ll have to start all over again” to which he excitedly exclaimed “I know!”.

Well, abandoning ship would throw this little nest-egg possibility right out the window (even if we were able to secure a commercial salvage). And “starting out all over again” held understandingly less excitement than before. Except when you figure that the “abandon ship” possibility of “starting out all over again” would be assuming we got out of this in one, well four, pieces (D, me, Mr. K and Will). That is, *if* the container ship would take us all aboard – “would they let us bring K aboard?.” Ugg, it’s ugly to think about leaving your “pet” in a situation like this (Katrina survivors, we tip our hearts to you).

Day 4, 6am

The sun is up. We know Seaboard Peru is coming for us. We don’t know what will happen when they get here. But being out of the darkness with help on the way feels literally like a brand new day.

However, now that it’s light, we can clearly see the sail, or rather, what’s left of it. Jeesh.

What now hangs from our forestay is not a jib but rather a series of white pennants – surrender much?

It seems clear that the whisker pole did in fact sever the leech line (the all-important string that runs through the outside of the sail) from the rest of the triangle, practically laying out a welcome mat for the wind to completely shred the sail.

With several sail repairs behind me, I jest “Think I can repair that?” to D, who simply curls his lip and mutters “go for it”. We slink into a corner of the cockpit and lick our wounds.

True, in the daylight everything always seems less dramatic. But, our “brand new day” feeling is waning. As we huddle in the corner of the cockpit, our practical questions (is everything packed in the ditch bags, etc) are replaced by the physiologically tormenting variety: why did we think we could pull this off? why are we putting ourselves and our families through this?, etc.

It’s easy to dream of “going cruising” – it’s all pina coladas, palm trees and sunsets, right? All we need to do is work out a budget and learn to sail!

Okay, so I knew it wouldn’t always be easy. I knew there’d be boat repairs we’d bemoan and scary storm stories we’d muscle through. But, losing the boat and starting over certainly wasn’t the picture on my screensaver at work for the last 3 years.

Needless to say, the morale aboard Mother Jones was pretty low at this point. But, I said (only to myself as to not jinx us further) “at least we’re not on fire . . .”

And, then, we saw her: Seaboard Peru coming for us over the horizon.

Even at 10 miles out, we could see she was HUGE – a container ship*. Uh oh. Everyone knows sailboats and container ships don’t normally mix, well. And, we were looking for a tow! I don’t think so . . . but we were stranded and willing to believe almost anything. Could it work? If it did, this would be one a helluva tow!

The Captain of Seaboard Peru made radio contact, notified us that the United States Coast Guard (USCG) was on their way and the ETA was 6 hours – noon. Hooray! In classic LFJ fashion, I thought hey, we’d get towed or fixed up with plenty of time to pull into Providencia before dark – we wouldn’t have to spend one more night on the water. Wouldn’t that be nice? It would be soooo nice.

Now that I knew help was on the way, I suppose I felt a bit greedy and wondered aloud to Damon when it would be appropriate to ask if they/someone could notify our family, that yes indeed, we were all fine and help was on the way. After all, it’s Sunday, Mother’s Day, and I’m pretty sure getting a distress call from your kids is kinda the worst Mother’s Day present ever. . .

But, a phone call home wasn’t to be. Seaboard Peru was quickly approaching and we had the next steps (???) to worry about.

*As it turns out, Seaboard Peru is 120m x 20m – or 525ft x 65ft – or 50 stories long and six stories high. That’s a big ship! At 34ft x 14 ft, Mother Jones is 10 times smaller!

Day 4, 6:30-7:30am

Soon, Seaboard Peru was within half a mile from us. We were happy to see them, but still completely in awe of their size – especially compared to ours. Staring up, up, up their hull, we couldn’t imagine how, exactly, they were going to help us. Sure, it’s possible they could come along side, throw us a line and then we’d bob merrily behind them. Key word: *possible*. Definitely not ideal. By all accounts, dangerous.

Sailors will tell you they avoid container ships like the plague. I certainly don’t want to paint everyone with the same brush: container ships (bad), sailors (good). But, generally when sailboats and containerships meet on the high seas, the sailboats lose. And, by “lose”, I mean the sailboats are completely destroyed.

Given this tumultuous reputation, we always went out of our way (like off course at least a mile) to avoid them. And, here we sat, bobbing along with a six-story-tall ship complete with a swirling, confused wash coming along side little Mother Jones.

Yep. I said it. THEY WERE COMING ALONGSIDE US.

The Captain came over the radio again instructing us that, yes, he was bringing Seaboard Peru about and (even though he’d never done it before!) we should be prepared to catch a line from their crew (only 3 stories up . . .) so we could raft up. Uh, sure, okay. Damon and I exchanged glances . . .

Let’s get this straight: we get within yards (YARDS!) of your steel hull, catch a long rope and then what??? Even if this was completed, surely, our fiberglass hull would be no match for theirs and tethered together, we’d just smash to bits. Or, even better, in the process of being dragging behind, we’d be sucked into the wash behind the ship. Um, no thanks.

We radioed back: “Seaboard Peru, this is Mother Jones. Um, we’re not *comfortable* with this plan of action. Please keep your distance”.

It was almost comical. Almost.

At this time practically all of the dozen Seaboard Peru crew were on the port side gangways. A few were actively trying to help us, trying to get in position to toss us 100 feet(!) of line, the others armed with their cameras (seriously?). I was in position on the starboard rail ready to catch the line (seriously?), harnessed in, in a dress(!), eyeballing their steel hull and swirling wash allthewhile yelling at D that this was increasingly looking like a bad idea. D was furiously at the wheel coaxing every bit of our intermittent engine and steering to get clear. And, Will? After telling him to get ditch bags ready, he was holed up in the head with a case of the nerves. Oh, and Kemah, he was cool as a cucumber.

We came within about 100 yards of the ship – too close for comfort for sure — before finally breaking loose and slowly, yet furiously, motoring to a safe distance.

Seaboard Peru offered to come about and try again. Um, no thank you!

Clearly, a Plan B was in order.

We learn from the Captain that according to maritime law, Seaboard Peru has been instructed by the USCG to serve as an escort for us, keeping an eye on us to make sure we were stable until they arrive. So, we float away, out of their huge chaperone shadow into a comfortable distance and wait.

Day 4, 8am

It’s been light for several hours, help is just over there and on the way. Boy, are we lucky. And, we know it. D and I huddled once again in the cockpit and reviewed what got us in this literal and figurative boat. We console each other with “all paths in life have risk” sentiments as well as “let’s just move back to dirt where this doesn’t happen” promises. Tears were shed and jokes were cracked but mostly we were just grateful.

Sometime during our navel-gazing, we were jerked eyes forward again by Seaboard Peru on the VHF. The Captain informed us that the USCG was delayed. They’re new ETA is eight hours from now – 4pm. Okay.

Don’t get us wrong, we were elated they were still coming. But, man, were we looking forward to seeing them at noon. Any chance that we’d be able to see land before dark (how was still a mystery . . .), before the forecasted bad weather for Sunday night was shot.

But, they’re the Coast Guard, right? Surely they’ll be able to tow us with their Cutter and they’ll know the way in the dark, right? Right???

And, so it went: a long day of hoping and waiting.

Day 4, 2:30pm

The radio crackles on “Mother Jones, Mother Jones, this is USCG Cutter Resolute”. Yes!!!!!

We go back and forth with them as they confirm our location and general condition including the nature of our mechanical problems, the health and state of mind of the crew , the kinds of emergency equipment we have, our sailplan, the amount of water and food we have on board, etc.

With each back-and-forth of the radio our spirits are buoyed but, of course, we still have questions about what’s to come.

They let us know they’re about 90 minutes out and we should sit tight (no problem). “Relieved” doesn’t describe the feeling, which came just before the feeling of “oh shit”, we’ve got official “guests” coming aboard soon. And, just like that we sprang into action clearing wet cushions and safety equipment from their former maze.

While we were all totally exhausted from the ordeal, it was all we could do to sit on our hands as we scanned the horizon for Resolute’s arrival on the scene.

Day 4, 4pm

From the north, we saw her, USCGC Resolute, coming behind Seaboard Peru – hallelujah!

With the experts on the scene and after eight hours of off-schedule chaperone duties, Seaboard Peru was ready to leave. They politely yet clearly requested permission from the USCG to resume course, not once, but twice. To which the USCG replied something to the effect of “hang tight until we’re a little closer” to the exasperated Captain of Seaboard Peru. Then it dawned on us: of course! Seaboard Peru preferred us to abandon ship because then they could stay on schedule (and not lose major cha-ching). And, then it’d be up to us to hire a commercial salvage team to recover our (seaworthy) vessel. Yup. We don’t really blame them but we’re glad we trusted our instincts, stayed with our (seaworthy) boat and super-glad there’s a USCG Cutter within sight.

Speaking of which . . . Resolute lets us know they’re sending three engineers to us aboard a small craft they’re lowering from the Cutter. What.a.sight.

The “small craft” they speak of? Wow! It’s like a batmobile of a dinghy. Holding the three engineers, a couple pilots and a few support crew, this “dinghy” reaches the mile between us and the Cutter in a few minutes through eight foot seas. It’s amazing. And, I should add, the pilot was amazing.

After zooming around Mother Jones to find the best entry point, they nosed up to our starboard swim steps and just like that, the engineers stepped aboard. STEPPED ABOARD, like it was nothing. Yep, no biggie, just going to nose a small craft up to a catamaran in eight foot seas and hop aboard. Typical work day.

Needless to say, we were impressed (of course).

Right from the start Eric, Allen and Mark got down to business helping us troubleshoot our problems. Allen and Mark started on the engine and Eric on the steering and then they all traded stations as needed. It was like a pit crew came aboard. It was all we could do to stay out of the way while answering their questions (you know how you feel dumb when making “that noise” to the mechanic, well multiply that times 100).

Even though Allen and Mark immediately suspected bad gas, they weren’t getting the kind of sputtering/not working at all issues we had for the last three days. And, Eric, he could get some steering, too. Isn’t that always the way!?! Of course, as soon as they came aboard, our problems seemed miraculously fixed! While we were relieved to have functioning systems, we didn’t trust it (afterall, we wouldn’t have called the Coast Guard if everything was fine). And, we certainly didn’t want them to leave just to have our problems arise again once they were out of VHF range.

(Un)fortunately after about thirty minutes of “everything seems good” being radioed from the engineers back to the Cutter, our problems showed themselves; a strange relief, frustration and more troubleshooting ensued.

After a few hours, we started to get patched up.

Regarding the engine, Mark and Allen suspected and confirmed we got bad gas in Jamaica. The Cutter only had 10 gallons of gas onboard (almost everyone but us uses diesel) and generously gave us five, which we figured was enough to mix in and get us to Providencia.

Regarding the steering, we got it functional but it was clear that at least some of the teeth in our steering helm were stripped and we’d have to get a new kit as soon as we could find one (unlikely in Providencia).

As far as the headsail was concerned, well, there wasn’t much to do except reduce the windage as much as possible by tying up or cutting off as much as we could.

The last thing they patched up was our generator. Of course they did that J While we could’ve easily fiddled with replacing the pull-cord in Providencia, these guys decided to leave us in the best shape possible by hauling our (25lb) generator out of Mother Jones, onto the small craft, back to the Cutter and returned it good as new. Wow.

So, there we were. All patched up. Were we ready to go on our own? Not much had really been solved but we had few options and *seemed* to be limping along quite well. Afterall, at this point we only had 100 miles to go . . . (that’s both a long way and not so far, in case you were wondering . . .)

With the USCG guys still onboard, keeping a close watch on the reliability of our systems, we watched the sun sink lower in the sky. We chatted, I asked a ton of questions*, we got to know a little bit about each other and they even got to watch Kemah (harnessed into D, who was harnessed into the boat) go out on the bow to do his business before night fell. Allen even agreed to call my Mom to tell her we were safe and I was sorry about my crappy Mother’s Day gift – AMAZING!!!

*The USCG does not charge for rescues (it’s included in our taxes); they do not accept gifts, although they would appreciate it if we called our Congressmen and encouraged them to not cut funding; they do not get “a lot of folks like us” out there, they mainly do “law enforcement” (read: drugs, not people – I asked).

Day 4, 7:25pm

We all finally decided we were fit to part ways. Then, Eric informs us there was just one thing left to do: an inspection. Of course!

We were happy to be inspected by Eric and passed with a Gold Form (the 100% passing form). Phew!

And just like that we watched Eric, Allen and Mark hop off Mother Jones as easily as they hopped on several hours earlier. Away they went in their batmobile-of-a-dinghy.

We thanked them profusely, in person and on the radio. And, then, we were on our own again.

Day 4, 7:45pm

With our Coast Guard rescue literally behind us, we were happy to be looking forward (again) towards Providencia. Somehow, we had managed to cover some significant distance with the USCG and now only had 60 miles (10 hours) to go. At this rate, we’d reach Providencia by dawn, in fact, we’d have to slow down to not reach this unfamiliar anchorage too early. We were in pretty good spirits.

And then, just to tease us, the engine sputtered. What!?! Were we really going to have to call the Coast Guard right back!?!

We waited, it sputtered, but it was under control; a reminder that we weren’t out of the woods yet.

As the sun slipped finally below the horizon and Resolute’s lights faded away, there was only one thing to do: motor on into the night.

Day 5, Monday

6-7:30am

All through the night, on our watches, we three kept a close ear on the engine. It needed some pumps from time to time, but hung in there like a champ.

And then, just a few miles off of Providencia, the sun rose. Awwww. It bathed over us nice and slow and warm, cleansing us from our journey.

We had been warned to stay in the channel and follow the buoys to avoid the reeds and sure enough, we rounded the island and slipped into the harbor with little fanfare. Or so we hoped.

Given our early arrival, we thought maybe, just maybe the other cruisers in the bay wouldn’t notice us limping in, the top of our shredded headsail still whipping about. But, no such luck. Shortly after a quick back-and-forth with the harbor master, a friendly voice came over the radio: “Mother Jones, this is Dan on SeaStar. We saw you in Jamaica. It looks like you *might* have had a rough crossing. Let us know when you get settled in and if you need any help, we’ll be right over. ” How nice. Seriously.

Their warm welcome and their offer to come right over and help was exactly what we’ve come to know from the cruising community: everyone may not always like each other, but everyone is always willing to lend a hand for those in need. We love this about cruising.

Dan and Kathy continued to welcome us telling us what to expect when we checked in and where things were where around town – including where we could grab a cold one at the end of the day, *should* we need one. Umm, yes.

But, there was a lot to do and even though we were all pretty punch-drunk from the passage, we figured we were up, we should stay up as long as we could and, while we were up, we should get some stuff done.

Day 5, 11am

Amazingly, by lunchtime we had accomplished a ton: I made and we ate a we’re-alive-so-let’s-eat-an-awesome-breakfast breakfast, we were cleared through customs and immigration, the sail was off, the bilges were dry and anything that was wet was drying in the sun. We even had all the dishes done and it wasn’t even noon!

We spent the rest of the day wandering around town drinking ice-cold beverages, checking out the local bakery and just generally being alive and on land.

Of course, around every corner was a new cruiser who *just couldn’t wait* to hear about what/how/when things happened to us on our passage. We told each one it’d cost them a beer 😉

Day 5, 5pm

After an afternoon of wondering around sleepy Providencia – it was siesta afterall – we cleaned up a bit and dinghy’d over to the local cruiser joint, Bamboo, for happy hour. Hey, it was the only place in town with internet to call my Mom!

I checked in with her and she was glad to hear from us. It turns out she had been kept abreast of our ordeal by a SPOT emergency network staffer who was relaying info from the Coast Guard. Of course she had been worried, but still somehow managed to have a nice Mother’s Day with my brother and sister while awaiting news – what a lady, huh?

After checking in with my Mom, I finally relaxed.

While telling (and retelling) our story to the fine sailors at Bamboo, we treated ourselves to Colombia’s finest: Redd’s beer and seafood curry. Needless to say, it hit the spot.

Shortly after dinner, we retired to Mother Jones to lay down our bones for a good night’s rest.

And, just like that, it was all over.